Jurisdictions

- Bermuda

- Guernsey

- Bahamas

- Barbados

- Seychelles

- Liechtenstein

- Singapore

- British Virgin Islands

- Hong Kong

- Luxembourg

- Antigua

- Switzerland

- Cayman Islands

- Nevis

- New Zealand

- Belize

- Netherlands

- Ireland

- United Kingdom

- United Arab Emirates

- Mauritius

- Jersey

- Labuan

- Rwanda

- Gibraltar

- Marshall Islands

- Samoa

- Panama

- St Vincent & The Grenadines

- Austria

- Madeira

Industry Sectors

- Hedge Funds and Alternative Investments

- Citizenship and Residency

- International Tax Planning

- Islamic Finance

- Fintech

- Insurance/Reinsurance

- Investment Funds

- Trusts And Foundations

- Private Banking

- Wealth Management

- Philanthropy

- Offshore Securities Markets

- Sustainable Finance

- Family Offices

- Arbitration

- Regulation and Policy

- Comment

- Big Debate

- In the Chair

- Global Regulation & Policy

- Features

- Sector Research

- Jurisdictions

- British Virgin Islands

- Cayman Islands

- Belize

- Bahamas

- Guernsey

- Switzerland

- Bermuda

- Barbados

- Singapore

- Hong Kong

- Luxembourg

- Labuan

- Jersey

- United Arab Emirates

- Ireland

- New Zealand

- Netherlands

- Liechtenstein

- Mauritius

- Antigua

- Rwanda

- Austria

- Seychelles

- Anguilla

- Samoa

- Marshall Islands

- Gibraltar

- Nevis

- United Kingdom

- North America

- Canada

- Asia

- Africa

- Latin America

- Australasia

- Europe

- Industry Sectors

- Hedge Funds and Alternative Investments

- Citizenship and Residency

- International Tax Planning

- Islamic Finance

- Fintech

- Insurance/Reinsurance

- Investment Funds

- Trusts And Foundations

- Private Banking

- Wealth Management

- Philanthropy

- Offshore Securities Markets

- Sustainable Finance

- Family Offices

- Arbitration

- Regulation and Policy

08/09/21

Whither The Global Minimum Tax?

On Thursday, July 1st, 2021, the OECD announced that 130 jurisdictions had signed a statement in which they committed to negotiate two draft treaties that would, if concluded and implemented, change the way many large companies are taxed.

The prospective treaties were hailed as a victory for tax fairness: Britain’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak, asserted that they will ensure, “the right companies pay the right tax in the right places,” while US Treasury Secretary, Janet Yellen, claimed that they would end the “race to the bottom.”[i]

The two draft treaties, known as Pillar One and Pillar Two, are being treated as a package but they approach the issue of taxation from fundamentally different and, in some respects, mutually incompatible perspectives. Pillar One would reapportion some of the taxes on profits of the world’s largest multinational companies. Pillar Two, meanwhile, would introduce a global minimum tax on multinational companies with annual revenues of at least €750million.

It is unlikely that these agreements would achieve what their proponents claim. But Pillar Two especially would inflict considerable economic damage on the world economy in general and on certain IFCs in particular (though some IFCs in the EU may benefit), including those in the Caribbean region. While many details remain to be ironed out, this article offers an assessment of what those effects will be – and what might be done to address some of the defects of Pillar Two.

Pillar One

The original justification for Pillar One was that the global system of taxation that has been in place for the past century is not well-adapted to the digital economy. Specifically, it was argued that because digital companies often make sales from outside the jurisdiction of the end users, there is a mismatch between the jurisdictions in which services are supplied and those in which taxes on sales, VAT, and corporate income are charged.

Governments have already responded to this digitalisation by introducing changes to the way digital services are taxed. About 90 jurisdictions now require suppliers of such services to register for VAT or sales tax in the jurisdiction in which the services are supplied.[ii] In addition, more than 25 jurisdictions have introduced “digital services taxes” (DSTs) or other direct taxes on revenue derived in those jurisdictions.[iii] But the proliferation of such taxes has raised concerns, especially in the US, that digital services companies could end up being overtaxed.

The main solution being developed under the auspices of Pillar One is the introduction of a new taxing right that will apply to companies with annual revenue in excess of €20 billion and profits of at least 10 per cent. The taxing right, which would presumably replace existing DSTs, would apportion between 20 and 30 per cent of “residual profits” (defined as profits in excess of 10 per cent of revenue) of in-scope companies to jurisdictions in which those companies supply goods and services. (The precise amount of profit to be allocated, known as “Amount A”, and the rules for apportioning that profit have yet to be determined.)

While, in general, Pillar One will apply to companies as a whole, it also contains a provision permitting it to be applied to major divisions. The rationale for this is quite simple: Amazon. Amazon has a profit margin of 6 per cent, meaning that as a company it would not be in scope. However, its Amazon Web Services division has a profit margin of more than 10 per cent, which would put it in-scope under the division rule.

In principle, Pillar One could have applied to financial services companies, many of which have annual revenue in excess of US$20 Billion. That could have affected larger IFCs such as London and New York. However, under the provisional agreement of 1st July, regulated financial service companies are excluded (reportedly on the grounds that their sales in any jurisdiction are made through regulated local entities, so are presumed to pay the appropriate amount of tax in each jurisdiction in which they operate).[iv] As such, Pillar One is unlikely to have a significant effect on IFCs.

Pillar Two

In spite of also having started life as part of an attempt to address the challenges of digitalisation, Pillar Two’s main purpose is to prevent companies from shifting profits from high-tax to low-tax jurisdictions—and thereby reducing the amount of corporate income tax (CIT) they owe.

Most jurisdictions already have measures intended to discourage such profit shifting, including “controlled foreign company” (CFC) rules, which specify the circumstances under which a headquarters’ jurisdiction may tax the profits of subsidiaries in other jurisdictions. Numerous other rules have been developed largely to prevent companies from circumventing these CFC rules. For example, transfer pricing rules and related-party debt rules seek to prevent companies from shifting profits to lower tax jurisdictions by inflating the cost of Intellectual Property, goods, services, and debt provided by subsidiaries.

But many large corporations still manage to use various strategies to reduce the effective CIT rate they pay on foreign-sourced income. Hence Pillar Two, which would introduce a minimum effective CIT rate of “at least 15%” for companies with annual revenue over €750 million.[v] This Global Anti-Base Erosion (“GloBE”) tax would be enforced through two rules:

- Under the “income inclusion rule” (IIR), companies paying an effective CIT rate of less than 15 per cent may be required to pay a “top up” amount in the headquarters’ jurisdiction or, if the CIT rate in the headquarters’ jurisdiction is less than 15 per cent, subsidiary jurisdictions may impose such top-up taxes.

- Meanwhile, as a backstop to ensure companies domiciled in low-tax jurisdictions pay their 15 per cent minimum, the “undertaxed payments rule” enables jurisdictions from which payments are made to a headquarter company to deny deductions and/or impose top-up taxes on those payments.

In addition to the GloBE tax rules, Pillar Two establishes a “subject to tax rule” under which jurisdictions would impose a tax of between 7.5 per cent and 9 per cent of the average stated tax rate on certain transactions between related parties.

The premise of Pillar Two is, in essence, that companies should pay minimum levels of corporate income tax wherever they have a domicile regardless of the amount of goods and services they supply in those domiciles. If that sounds contrary to the aims of Pillar One, that is because it is. It is also contrary to the rules on economic substance that were developed as part of the OECD’s BEPS Actions—even though Pillars One and Two were negotiated as an extension of BEPS Action One.[vi] Pillar Two in its present form is essentially an attempt to cling onto an outmoded, inefficient and harmful form of corporate taxation by setting a minimum bound on tax competition.

Pillar Two could significantly affect IFCs, especially those in low tax and tax neutral jurisdictions, particularly in the Caribbean. However, the nature and extent of its effect will depend very much on both the details in the final agreement, which are still far from being worked out, and the ways in which jurisdictions respond.

The Devil In The Detail

In general, Pillar Two is likely to result in within-scope companies paying more CIT. Most of this CIT will be paid to a small number of large, high-tax jurisdictions, including the US, France, Germany, Italy, the UK and China.[vii] This will reduce the amount of residual profit available for investment which will have several knock-on effects: first, within-scope companies will likely become less innovative and grow more slowly; second, the pool of capital as a whole will be reduced, raising the cost of capital and leading to less investment and lower rates of innovation overall, with a consequent reduction in the rate of growth. Pillar Two will thus have a net depressing effect on IFCs in general.

One factor that could make this effect stronger or weaker is the way in which the GloBE effective tax rate is calculated. Until recently, two alternative methods were on the table: “global blending” and “jurisdictional blending”. Under global blending, a company’s effective tax rate is calculated by taking the sum of all CIT paid by the company worldwide and dividing that by its total profit. By contrast, under jurisdictional blending, the effective tax rate is calculated on a jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction basis; i.e. by dividing CIT paid in a jurisdiction divided by profits in that jurisdiction, taking into account any formulaic and/or jurisdiction-specific carve-outs.

Under global blending, within-scope companies can offset some of the taxes they pay in higher-tax jurisdictions by continuing to have operations in lower-tax jurisdictions. Under jurisdictional blending, this is not possible. So, within-scope companies will generally pay more tax under jurisdictional blending than under global blending. In addition, compared with global blending, jurisdictional blending would impose much higher administration costs on both multi-national enterprises (MNEs) and tax authorities. For many jurisdictions, the costs of implementing jurisdictional blending would be significantly greater than the amount of tax raised.

For these reasons, relative to global blending, jurisdictional blending would result in a greater increase in the cost of capital and a greater reduction in inward investment.[viii] As a result, jurisdictional blending would lead to lower rates of innovation and economic growth. In other words, jurisdictional blending would do greater harm to the world economy. It would also do much more harm to some IFCs located in low-tax and tax neutral jurisdictions.

But both companies and governments will respond differently under global blending than under jurisdictional blending. For example, the following are likely responses to Pillar Two—but are considerably more likely under jurisdictional than under global blending:

- Some MNEs will move their headquarters from higher- to lower-tax jurisdictions in-order to reduce their total tax burden, depriving those higher-tax jurisdictions of the top-up tax.

- Some lower-tax jurisdictions will raise their tax levels (at least for within-scope MNEs) to the GloBE minimum, in order to capture the tax that would otherwise be paid in the jurisdiction of the headquarters. (This is rather unlikely under global blending but seems a highly likely outcome under jurisdictional blending.)

- New taxes imposed in other jurisdictions in line with GloBE could result in additional domestic tax deductions, thereby reducing domestic tax revenue in Ultimate Parent Entity (UPE) jurisdictions.

Based on all the above, global blending might seem like the obviously better policy. In addition, the US currently applies global blending to determine the effective tax rate of corporations paying the minimum tax on some overseas-derived corporate income under the Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) rule (part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act). As such, until this year there was some expectation that in order to bring the US on board, Pillar Two would adopt a global blending approach. (The UK also applies a version of global blending under its current CFC rules, so it might have been expected to have been more supportive of global blending too.)

But the obviously better policy is often not the politically expedient policy. In the OECD’ s Blueprint for Pillar Two released last year, the focus was firmly on jurisdictional blending, suggesting that it has been the favoured option for some powerful vested interests (likely including France, Germany and Italy) for some time.[ix] Meanwhile, in his America Jobs Plan Act, President Biden is seeking to change the blending rule in GILTI from global to jurisdictional. And Biden pushed hard for the G7/G20/Inclusive Framework countries to adopt jurisdictional blending. In June, the G7 Finance Ministers stated that they had agreed on a “jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction” approach, i.e. jurisdictional blending, and this was adopted by the G20 and 130 members of the OECD Inclusive Framework in the Statement of 1st July.[x]

Wild Cards

While it would appear that global blending is thus off the table, this might change if the US does not amend GILTI, since the US could then not implement Pillar Two if it were based on jurisdictional blending. And if the US does not implement Pillar Two, then US firms would be at a substantial advantage relative to firms based in other high-tax jurisdictions, so either the entire agreement could fall apart or there would be substantial pressure to shift to jurisdictional blending in order to get the US on board.

Another wild card is the EU. While large, high-tax EU members have been among the strongest proponents of a global minimum CIT, smaller, lower-tax jurisdictions within the Union have vehemently opposed it. Ireland (which has a 12.5 per cent CIT rate and attractive IP box and CAIA programme), Hungary (which has a flat CIT rate of 9 per cent), and Estonia (which exempts most undistributed profits from income tax and applies a CIT of 14 per cent to enterprises that pay a regular dividend), have not signed up to the global minimum tax. Meanwhile Cyprus, which has a CIT of 12.5 per cent but which is not a member of the OECD Inclusive Framework, has also expressed opposition. This should worry proponents of a minimum tax because under settled EU law, Pillar Two could be construed as a violation of two of the EU’s constitutionally protected fundamental freedoms: the freedom of establishment and free movement of capital.[xi] As such, for any EU jurisdiction to apply Pillar Two to another EU member state would require at-minimum a new Directive and possibly an amendment to the constitution. In either case, unanimity would be required – and that would not appear to be forthcoming.

But even if EU member states are not permitted to apply Pillar Two to one another, they might still be able to apply it to third countries. As such, the agreement could lead to the perverse result that top-up taxes are imposed on EU-domiciled companies’ subsidiaries in low-tax third countries but not on their subsidiaries in low-tax EU states. If that were the case, it is likely that at least some of those subsidiaries would move their domicile to the EU, including Bermuda, BVI and Cayman, to an EU member state. In terms of the effect on IFCs, such an outcome would benefit EU-based IFCs at the expense of IFCs in the Caribbean and other locations.

Some Funds Might Get Caught by GloBE

Pillar Two might also, perversely, lead to a substantial increase in double taxation—which is clearly contrary to the claim that it taxes the right companies in the right places. The Blueprint explicitly states:

“The need to preserve the tax neutrality in respect of investment funds is a widely recognized principle that underpins the design of the international tax rules. … The neutrality of funds is a specific and generally supported tax policy rationale, which would be undermined if the GloBE rules were applied to the income of the fund resulting in an otherwise tax neutral investment vehicle being subject to an additional layer of taxation under the laws of another state. Given this approach is already widely adopted in domestic taxation systems, an exclusion for investment funds from the GloBE rules also does not provide a competitive advantage or create economic distortions. It is therefore appropriate to preserve the tax neutrality policy, by ensuring that fund vehicles are not exposed to the GloBE rules”.[xii]

Unfortunately, the definition of “investment fund” in the Blueprint may be too narrow to cover many funds that should be treated as tax neutral. Specifically, the Blueprint includes in its definition the condition that “the fund, or the management of the fund, is subject to the regulatory regime for investment funds in the jurisdiction in which it is established or managed (including appropriate anti-money laundering and investor protection regulation)”. In addition, “The definition also includes any entity or arrangement that is wholly-owned or almost exclusively owned, directly or indirectly, by one or more Investment Funds or other Excluded Entity and that does not carry on a trade or business but is established and operated exclusively or almost exclusively to hold assets or invest funds for the benefit of such Investment Funds or other Excluded Entity”.

While this definition may be broader than some that could have been adopted, it is still too narrow. Among other things, it does not explicitly include unregulated funds. Meanwhile, funds that consolidate with investors and/or lower-tier entities and meet the revenue threshold could be deemed to be MNEs within the scope of the GloBE rules.

As such, some holdco funds, private equity funds, insurance company funds, and unregulated (private) funds might be deemed to be within the scope of GloBE. This could lead to serious distortions. The best solution would be to expand the definition of an excluded fund to cover all these entities. If that is not done, some fund holders would likely develop workarounds to avoid double taxation. But for those that are unable to use such workarounds, the cost could be large. Given the large number of funds that are domiciled in tax neutral IFCs, the failure to exclude all funds could have a significant effect on certain sectors in some IFCs.

A Race To The Bottom – Or To The Top?

A more fundamental question is whether Pillar Two is desirable at all. Proponents of a global minimum effective CIT claim that jurisdictions have been competing with one another to reduce CIT, resulting in a “race to the bottom” that has eroded the tax base, making it more difficult to supply needed government services. But has there really been such a “race to the bottom”?

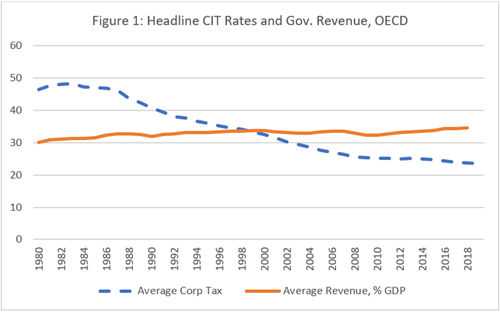

Figure 1 shows that since 1980, headline CIT rates in the OECD have fallen from an unweighted average of over 45 per cent to below 25 per cent. Over the same period, government revenue as a proportion of GDP has risen from about 30 per cent to about 35 per cent. Clearly, the decline in CIT rates has not led to a fall in government revenue.

Source: OECD

From an economic perspective, the push for a global minimum effective CIT rate is perverse because the overwhelming body of evidence suggests that CIT is the most economically harmful form of tax – and the higher the effective rate of CIT, the more harmful it is. Indeed, a study by a group of OECD economists that analysed the effect of different types of tax found that:

“Corporate taxes are found to be most harmful for growth, followed by personal income taxes, and then consumption taxes. Recurrent taxes on immovable property appear to have the least impact. A revenue neutral growth-oriented tax reform would, therefore, be to shift part of the revenue base from income taxes to less distortive taxes such as recurrent taxes on immovable property or consumption”.[xiii]

Another study by a team led by world-renowned economist and former Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance of Bulgaria, Simeon Djankov investigated the effect of corporate taxes on the same standardised mid-size business in 85 different countries. After accounting for myriad other factors, the authors found that:

“The effective corporate tax rate has a large adverse impact on aggregate investment, FDI, and entrepreneurial activity. For example, a 10 per cent increase in the effective corporate tax rate reduces aggregate investment to GDP ratio by 2 percentage points. Corporate tax rates are also negatively correlated with growth, and positively correlated with the size of the informal economy”.[xiv]

And a recent study published in the Journal of Accounting and Economics found, “a strong robust negative relation between country-level effective tax rates and future macroeconomic growth”.[xv] These and other similar studies suggest that lower effective rate of corporate income tax results in increased investment, entrepreneurial activity, and ultimately economic growth.

Studies looking at changes in taxes over time come to similar conclusions. A notable study co-authored by Christina Romer, who chaired President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisors, evaluated the effects of all major tax changes in the US made after WWII and found that a tax cut of 1 per cent of GDP increased GDP by between 2.5 per cent and 3 per cent -- and that between 45 per cent and 90 per cent of corporate tax cuts were self-financing.[xvi] Similarly, a recent study of the macroeconomic effects of tax changes in the EU found that a tax cut of 1 per cent of GDP results in a cumulative increase in GDP over five years of approximately 2 per cent when the tax is unanticipated and approximately 0.66 per cent when the tax is anticipated.[xvii]

Meanwhile, empirical analysis of the effects of changes to the structure of taxation show that increases in consumption taxes and VAT have a less detrimental effect on growth than increases in CIT, as does the broadening of the tax base through the removal of tax deductions and incentives.[xviii]

These studies suggest that over the past 40 years, the reduction in CIT rates in OECD countries and concomitant shift in the tax base towards less harmful forms of taxation, such as VAT, has stimulated economic growth which in turn has enabled governments to increase revenue in ways that are less economically harmful. In other words, the decline in CIT rates in the OECD has not resulted in a “race to the bottom”. Au contraire, from an economic perspective, it has resulted in a race to the top as countries compete to have better systems of taxation.

Avoiding Lock-In To A Harmful Tax

By fixing the global minimum tax at 15 per cent , the OECD Inclusive Framework (acting in the name of the 132 jurisdictions that have now notionally “signed” the agreement) presumptively asserts that the optimal CIT rate is at least 15 per cent. But as noted above, the economic evidence—including that from the OECD itself—suggests that the optimal CIT rate is much lower (and may actually be zero). So, locking the world into what is almost certainly a suboptimal minimum CIT rate seems like a very bad idea. Worse, numerous jurisdictions and organisations have already declared that they would like to see the minimum tax rise over time.[xix] Meanwhile, as noted, some lower-tax jurisdictions have declared that they won’t join the minimum tax. So, there is a serious risk of adverse selection, with higher tax jurisdictions gradually driving the minimum CIT higher and lower tax jurisdictions not ratifying or leaving the system. The risk of this materialising is magnified by the non-democratic way decisions are made in intergovernmental forums such as the OECD and the so-called “Inclusive Framework” (the group of 139 jurisdictions that signed on to the BEPS Actions), whereby larger, higher-tax jurisdictions such as the US are able to dominate by threatening sticks and offering carrots to smaller, lower tax jurisdictions.

One way to overcome or even reverse this adverse selection would be to apply a similar rule to the one the UK currently applies, namely, to set the global minimum effective tax rate in proportion to the current global average effective tax rate. For 2019, the average effective tax rate of the 73 jurisdictions for which data is available was 20.3 per cent. So, if the global minimum effective CIT were set at, say, 50 per cent of the average effective CIT rate, that would mean a current rate of 10 per cent. This would encourage all jurisdictions with effective CIT rates of 10 per cent or more to ratify the global minimum tax agreement. But if jurisdictions continue to lower their rates, the global minimum would continue to fall.

The Statement of 1st July now has 132 “signatories”.[xx] But what have they actually signed up to? While the UK, US, G7, G20 and OECD all issued statements asserting the historic significance of the decisions made at various points in June and July, the reality is that much of the substance of the two treaties has yet to be developed. And some of the substance that does seem to have been agreed has been met with such disapproval by several key jurisdictions that they refused to sign up. The size of the tax is clearly a stumbling block for some (Ireland, Hungary, Cyprus), while the limited substance-based carve out is likely a problem for Estonia. Moreover, some elements (the blending method, for example) might end up being reopened if the US does not change its own rules. Some other holdouts seem more focused on what are euphemistically called “side payments”.

The G20 has committed to negotiating a more comprehensive agreement on Pillar Two by the full G20 meeting in Italy in October. That timeframe, which appears to be driven by the US, may be too ambitious if the intention is to reach unanimity among the 139 Global Framework countries. If unanimity is the objective, then shifting to global blending, permitting full expensing, changing the calculation of the tax to a proportionate system, and setting the proportion such that the global minimum effective tax rate is closer to 10 per cent seem like strategies worth pursuing. But perhaps unanimity is not the objective, any more than is the assertion that these new agreements will ensure that the right companies pay the right taxes in the right places.

Footnotes:

[i] https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/05/us/politics/g7-global-minimum-tax.html

[ii] As of July 22, 26 countries have implemented digital services taxes and more than a dozen have either drafted legislation or announced plans for implementation. https://tax.kpmg.us/content/dam/tax/en/pdfs/2021/digitalized-economy-taxation-developments-summary.pdf

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/statement-on-a-two-pillar-solution-to-address-the-tax-challenges-arising-from-the-digitalisation-of-the-economy-july-2021.pdf; https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/uk-wins-financial-services-carve-out-new-global-tax-rules-ft-2021-06-30/

[v] As discussed, Pillar Two actually comprises not only the global minimum tax rules (known formally as the Global anti-Base Erosion (GloBE) rules) but also a subject-to-tax rule.

[vi] https://www.oecd.org/ctp/BEPS-FAQsEnglish.pdf

[vii] See e.g.: https://ecipe.org/publications/unintended-undesired-consequences/

[viii] https://www.sbs.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-02/OECD_GloBE_proposal_report.pdf

[ix] https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/tax-challenges-arising-from-digitalisation-report-on-pillar-two-blueprint-abb4c3d1-en.htm

[x] https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/statement-on-a-two-pillar-solution-to-address-the-tax-challenges-arising-from-the-digitalisation-of-the-economy-july-2021.pdf

[xi] Case C‑196/04 Cadbury Schweppes v Commissioners of the Inland Revenue. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=ecli%3AECLI%3AEU%3AC%3A2006%3A544

[xii] OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Report on Pillar Two Blueprint, Paris: OECD, 2020, at p. 34. https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/tax-challenges-arising-from-digitalisation-report-on-pillar-two-blueprint-abb4c3d1-en.htm

[xiii] https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/taxation-and-economic-growth_241216205486

[xiv] https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/mac.2.3.31

[xv] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0165410119300205

[xvi] https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.100.3.763

[xvii] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264999319308296?via%3Dihub

[xviii] https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2018/09/28/Macroeconomic-Effects-of-Tax-Rate-and-Base-Changes-Evidence-from-Fiscal-Consolidations-46250

[xix] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2021/06/06/france-tells-g7-hike-minimum-tax-rate/

[xx] https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/oecd-g20-inclusive-framework-members-joining-statement-on-two-pillar-solution-to-address-tax-challenges-arising-from-digitalisation-july-2021.pdf

About the Author

Julian Morris FRSA Julian Morris has 30 years’ experience as an economist, policy expert, and entrepreneur. In addition to his role at ICLE, he is a Senior Fellow at Reason Foundation and a member of the editorial board of Energy and Environment. Julian is the author of over 100 scholarly publications and many more articles for newspapers, magazines, and blogs. A graduate of Edinburgh University, he has masters’ degrees from UCL and Cambridge, and a Graduate diploma in law from Westminster. In addition to his more academic work, Julian is an advisor to various business and a member of several non-profit boards.