Jurisdictions

- Bermuda

- Guernsey

- Bahamas

- Barbados

- Seychelles

- Liechtenstein

- Singapore

- British Virgin Islands

- Hong Kong

- Luxembourg

- Antigua

- Switzerland

- Cayman Islands

- Nevis

- New Zealand

- Belize

- Netherlands

- Ireland

- United Kingdom

- United Arab Emirates

- Mauritius

- Jersey

- Labuan

- Rwanda

- Gibraltar

- Marshall Islands

- Samoa

- Panama

- St Vincent & The Grenadines

- Austria

- Madeira

Industry Sectors

- Hedge Funds and Alternative Investments

- Citizenship and Residency

- International Tax Planning

- Islamic Finance

- Fintech

- Insurance/Reinsurance

- Investment Funds

- Trusts And Foundations

- Private Banking

- Wealth Management

- Philanthropy

- Offshore Securities Markets

- Sustainable Finance

- Family Offices

- Arbitration

- Regulation and Policy

- Comment

- Big Debate

- In the Chair

- Global Regulation & Policy

- Features

- Sector Research

- Jurisdictions

- Back

- Barbados

- Cayman Islands

- British Virgin Islands

- Singapore

- Guernsey

- Bahamas

- Hong Kong

- Switzerland

- Luxembourg

- Liechtenstein

- Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Bermuda

- Jersey

- Ireland

- Rwanda

- Belize

- Labuan

- United Arab Emirates

- Mauritius

- Antigua

- Austria

- Seychelles

- Anguilla

- Samoa

- Marshall Islands

- Gibraltar

- Nevis

- United Kingdom

- North America

- Canada

- Asia

- Africa

- Latin America

- Australasia

- Europe

- Turks & Caicos Islands

- Industry Sectors

- Back

- Hedge Funds and Alternative Investments

- Citizenship and Residency

- International Tax Planning

- Islamic Finance

- Fintech

- Insurance/Reinsurance

- Investment Funds

- Trusts And Foundations

- Private Banking

- Wealth Management

- Philanthropy

- Offshore Securities Markets

- Sustainable Finance

- Family Offices

- Arbitration

- Regulation and Policy

22/02/23

From Sector Research

Offshore FDI, Tax Havens And Productivity: A Network Analysis

By Soni Jha, Department of Strategic Management, Fox School of Business, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; and Snehal Awate, S. J. Mehta School of Management, Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Bombay, Mumbai, India.

Tax havens play a big part in the movement of global investment flows as Multinational Companies (MNCs) use them extensively in their tax planning. They are however targeted in the popular media and by governments for distorting global financial markets, eroding national corporate tax bases, and reducing the overall productivity of the countries. Due to this negative narrative around the use of tax havens by the MNCs, the home and host country governments often enforce policies to impede their role in foreign direct investments (FDI). While the policy barriers are raised on one side, MNCs, on the other side, find ways to disperse their tax haven activities and invest in multiple tax havens.

In our research, we show that all offshore FDI is not unproductive. As managers route their investments through multiple tax havens, their home countries may experience productivity losses, but the host countries receive productivity gains. Further, the use of central, well-established tax havens brings productivity gains to both home and host countries. By treating tax haven ties as all equal and all bad, the countries may forego these productivity gains. Our results become particularly salient against the backdrop of the international tax harmonisation system, championed by the OECD and agreed by 136 countries, which represent about 90 per cent of the world’s GDP.

Introduction

MNCs use FDI in tax havens to benefit from tax arbitrage opportunities. However, this quick arbitrage strategy leads to inefficient allocation of FDI and negatively affects its potential for global value creation (Foss, Mudambi, & Murtinu, 2019). Offshore investments in tax havens may not culminate into any value-added activities in the host countries (Beugelsdijk, Hennart, Slangen, & Smeets, 2010), because MNCs use their tax haven affiliates to appropriate profits from high tax jurisdictions and reduce their tax burden, rather than engage in actual production activities (Casson, 2022; Hennart, 2011; Ting & Gray, 2019). As a result, both home and host countries often enforce policies that impede the ability of MNCs to use tax havens. MNCs have responded by increasing the complexity of their value chain activities and using multiple tax haven locations to exploit tax arbitrage opportunities (Eden, 2009; Foss et al., 2019; Nebus, 2019; Ting & Gray, 2019). Our research assesses the effect of increasing dispersion of MNC activities and their use of multiple tax haven locations on the productivity of home and host countries.

We model the global offshore FDI network using aggregate country-level data that showcases the MNCs' behavioural responses to increased taxation by increasing the dispersion of their tax haven activities. Using a sample of 212 countries from 2001 to 2012, we measure the structural positions of the MNCs' home and host countries in the offshore FDI network. We consider two types of tax haven ties, namely (i) outgoing ties to tax havens from the MNCs' home countries, and (ii) incoming ties from tax havens into the host countries. This approach helps us distinguish the effects of increasing dispersion in outgoing and incoming ties on the home and the host countries, respectively. The dispersion in ties is measured using the degree centralities of the countries.

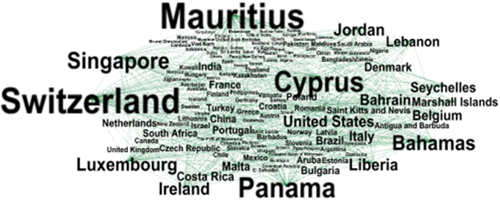

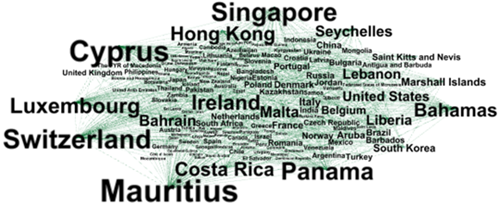

This network approach also shows the true multilateral nature of these investments. For example, Figure 1 shows the offshore outward FDI (OFDI) network and countries’ degree centralities. Since it is a directed network, higher connectivity of home countries implies their MNCs are investing large amounts in several tax havens, and higher connectivity of tax haven countries implies that they receive large investments from several home countries. A larger font indicates the countries with higher degree centralities. Figure 2 similarly shows the offshore inward FDI (IFDI) network where the larger font indicates the countries with greater degree centralities. Both figures depict the stark reality of the global FDI, where a large number of MNCs from multiple countries use tax havens. We observe that the magnitude of FDI arriving in and leaving from tax havens is much larger than non-tax haven countries. For example, the US, which is a major home country of MNCs, appears much smaller when compared to the tax havens in the OFDI network in Figure 1. Similarly, a major host country like China appears smaller when compared to the FDI received by tax havens in Figure 2.

Figure 1: Offshore OFDI network for the year 2012

Figure 2: Offshore IFDI network for the year 2012

Effect Of Outgoing Ties To Tax Havens

We argue that the home countries' ability to monitor and prevent the loss of capital to tax havens depends on the structural position of the home country in the offshore OFDI network. Being central in the offshore OFDI network means that investments from the home country are directed towards more tax haven destinations than peripheral countries. Also, the size of the investments from centrally located countries is larger than those from peripheral countries. As MNCs of central countries invest in more tax haven locations, it becomes more difficult for their home country to trace the degree and magnitude of their offshore investments (Kemme, Parikh, & Steigner, 2017). In the absence of global tax agreements or treaties, home countries try to stem the erosion of corporate tax bases by signing an increasing number of bilateral international tax treaties (Van 't & Lejour, 2014). However, bilateral treaties only partially remedy the systemic issue of tax evasion by MNCs, leading to a vicious cycle. MNCs respond to bilateral treaties by further dispersing their tax haven activities, which further increases the centrality of their home country in the offshore OFDI network.

The ability of these central home countries in controlling the outflow of capital to tax havens is limited, compared to home countries located at the peripheries of the offshore OFDI network, which have fewer and weaker linkages to the tax havens. As the countries become more entrenched in the offshore OFDI network, the constraints they face to extricate themselves by severing ties to tax havens increase. This increases the persistence and magnitude of productivity losses on account of their ties to tax havens. Accordingly, we find that increasing the dispersion of outgoing ties, or the degree centrality of the MNCs' home country in the offshore OFDI network, is associated with a decrease in the productivity of the home country.

Effect Of Incoming Ties From Tax Havens

MNCs often invest in tax havens to avoid taxation on accrued profits (Eden, 2009), or other financial or intangible assets (Lipsey, 2003), leading scholars to argue that FDI routed through tax havens does not culminate into any productive activity or value addition for the host country (Beugelsdijk et al., 2010). However, capital intermediated through tax havens moves beyond its jurisdictions (Weichenrieder & Mintz, 2008). Due to this global movement of capital, even when tax haven activities are locally suboptimal, they may be globally optimal, and thus, their overall effect could be positive (Hong & Smart, 2010). This is because the MNC investments to and from tax havens depend on the heterogeneous costs of mobilising capital across borders (Keen, 2001). MNC affiliate activity in tax havens may thus denote capital flows for which cross-border transaction costs were higher than the tax planning costs. It is plausible then that the inward investment from tax havens reflects optimised capital movements or capital that would have been otherwise immobile or inefficient.

Host countries central in the offshore IFDI network receive more investments and from multiple tax haven locations. Since the efficiency of capital from tax havens is higher, centrally located host countries have a greater opportunity to increase their capital efficiency than peripherally located host countries, because they receive a greater volume of capital flows from tax havens. In addition, host countries compete to attract MNC investments (Mudambi, 1998), often with respect to tax rates (Wilson & Wildasin, 2004), and thus offer tax incentives (Raff, 2004), which become the cost of tie formation. Host countries centrally located in the offshore IFDI networks are better placed in the competition for attracting inward FDI than peripheral countries. Central host countries have higher bargaining power, which lessens tax competition for them, and reduces their incentive to give preferential tax treatments to MNCs, compared to peripheral countries. In other words, increasing centrality increases the volume of capital flows to host countries and lowers their cost of attracting MNC investments. Accordingly, we find increasing dispersion of incoming ties, or the degree centrality of the MNCs' host country in the offshore IFDI network, is associated with an increase in the productivity of the host country.

Effect Of Connecting To Prominent Tax Havens

We distinguish between the effects of ties to peripheral tax havens, such as Bermuda, versus central or more prominent tax havens, such as Switzerland, using the eigenvector centralities of the countries. The MNC's global strategy ultimately considers the final capital efficiency achievable through tax planning. MNCs also use tax havens for their significant financial expertise and well-developed legal infrastructure to increase their capital efficiency (Dharmapala & Hines, 2009; Rose & Spiegel, 2007). Central tax havens receiving investments from MNCs from multiple countries also experience scale effects, which further increases their financial expertise. Instead of simply routing the investments, the firms in well-developed, central tax havens can offer advice and experience to MNCs on their host country investment decisions, such as selecting targets, locations, value chain activities, alliance partners, suppliers, and so on. Thus, MNCs are also likely to be attracted to well-developed central tax havens for greater capital efficiency. They are also likely to maintain a presence in well-developed tax havens to obtain investment leads, showcase their capabilities, facilitate and escort the investments back home.

While capital may still leave the country, home countries' tracking costs are likely lower when their MNCs invest in central tax havens with well-developed legal institutions. The home country may even be more accepting of the benefits of investing in central tax havens by its MNCs, and devise consultative measures agreeable to all. These measures include reinvestment treaties, tax breaks for bilateral investments between the home country and the tax haven, attracting specialised sectoral investments, and investment from other countries whose MNCs may be present in the central tax haven. We find that by connecting to more central tax havens and improving its prominence in the offshore OFDI network, countries experience greater productivity.

Conclusion

The strong forces of globalisation and the advances in digitalisation have significantly increased the ability of MNCs to mobilise their capital across national boundaries in a more frictionless manner (Autio, Mudambi, & Yoo, 2021). We find this trend toward dispersion of MNC activities also in their tax planning decisions, as they use more tax havens more heavily. While this strategy may affect home country productivity, it improves the productivity of the host country. More importantly, by connecting to prominent, well-established tax havens, both home and host countries receive productivity gains.

Our additional robustness analyses show that the effects of tax haven ties vary depending on the country's income level and development status. The results imply that the common international tax system needs to incorporate tax gradation for central versus peripheral tax havens, and accommodate countries with different income and development statuses.

Original source: Jha, S., & Awate, S. Offshore FDI, tax havens, and productivity: A network analysis. Global Strategy Journal, Early View - https://doi.org/10.1002/gsj.1466

References:

Autio, E., Mudambi, R., & Yoo, Y. (2021). Digitalization and globalization in a turbulent world: Centrifugal and centripetal forces. Global Strategy Journal, 11(1), 3-16.

Beugelsdijk, S., Hennart, J. F., Slangen, A., & Smeets, R. (2010). Why and how FDI stocks are a biased measure of MNE affiliate activity. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(9), 1444-1459.

Casson, M. (2022). Extending internalization theory: Integrating international business strategy with international management. Global Strategy Journal, Early View. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/gsj.1450

Dharmapala, D., & Hines, J. R. (2009). Which countries become tax havens? Journal of Public Economics, 93.9(10), 1058–1068.

Eden, L. (2009). Taxes, transfer pricing, and the multinational enterprise. In A. M. Rugman (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of international business (2nd ed.), 591–619. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Foss, N. J., Mudambi, R., & Murtinu, S. (2019). Taxing the multinational enterprise: On the forced redesign of global value chains and other inefficiencies. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(9), 1644–1655.

Hennart, J. F. (2011). A theoretical assessment of the empirical literature on the impact of multinationality on performance. Global Strategy Journal, 1(1‐2), 135-151.

Hong, Q., & Smart, M. (2010). In praise of tax havens: International tax planning and foreign direct investment. European Economic Review, 54(1), 82–95.

Keen, M. (2001). Preferential regimes can make tax competition less harmful. National Tax Journal, 54(4), 757–762.

Kemme, D. M., Parikh, B., & Steigner, T. (2017). Tax havens, tax evasion, and tax information exchange agreements in the OECD. European Financial Management, 23(3), 519–542.

Lipsey, R. E. (2003). Foreign direct investment and the operations of multinational firms: Concepts, history, and data. Handbook of International Trade, 285-319.

Mudambi, R. (1998). The role of duration in multinational investment strategies. Journal of International Business Studies, 29(2), 239–261.

Nebus, J. (2019). Will tax reforms alone solve the tax avoidance and tax haven problems? Journal of International Business Policy, 2(3), 258-271.

Raff, H. (2004). Preferential trade agreements and tax competition for foreign direct investment. Journal of Public Economics, 88(12), 2745–2763.

Rose, A. K., & Spiegel, M. M. (2007). Offshore financial centers: Parasites or symbionts? Economic Journal, 117(523), 1310–1335.

Ting, A. & Gray, S.J. (2019). The rise of the digital economy: Rethinking the taxation of multinational enterprises. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(9), 1656 -1667.

Van 't, M., & Lejour, R. A. (2014). Ranking the stars: A network analysis of bilateral tax treaties. CPB discussion paper No. 290, CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis.

Weichenrieder, A. J., & Mintz, J. (2008). What determines the use of holding companies and ownership chains? Centre for Business Taxation Working Paper WP08/03, Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation.

Wilson, J. D., & Wildasin, D. E. (2004). Capital tax competition: bane or boon. Journal of Public Economics, 88(6), 1065–1091.

About the Author

Soni Jha

Soni is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Management at Temple University. Soni specialises in strategic management and international business.

About the Author

Dr. Snehal S. Awate

Dr. Snehal S. Awate is from the Faculty of Strategy at IIT Bombay. Snehal's areas of interest include competitive strategies of emerging economy multinationals, innovation networks, social network analysis, organisational learning and patent research.